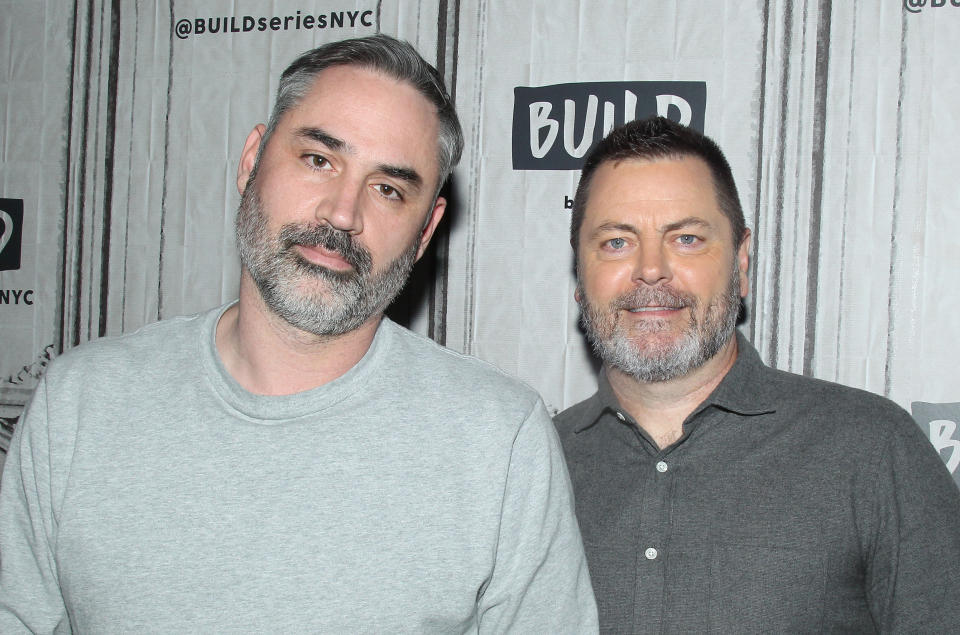

Alex Garland on 'Devs,' free will and quantum computing

The writer/director chats about his latest high-concept sci-fi project on FX/Hulu.

Alex Garland's Devs is unlike anything currently on television. The Hulu/FX show starts out as an exploration of a powerful tech company that has cracked the secrets of quantum computing, but it evolves into an exploration of free will, determinism and the nature of reality. Garland is no stranger to big questions -- his first film, Ex Machina, tackled the intricacies of AI consciousness. He turned Jeff Vandermeer's practically unfilmable novel Annihilation into a surreal and nightmarish adaptation about personal identity. And as the screenwriter of 28 Days Later and Sunshine, he earned a reputation for viewing science fiction with an intelligent eye.

[Listen to our full Alex Garland interview on the Engadget Podcast! Subscribe to the show on iTunes and Spotify!]

"Devs is like a companion piece to Ex Machina," Garland said in an interview with Engadget last week. "I had a set of concerns, some of which were cross related to Ex Machina, and some of which were discrete to Devs. With Devs, it was triggered by this concept of determinism and trying to present a couple interpretations of quantum mechanics. That sounds like an inherently complex statement, but it isn't really. Quantum mechanics is the term that's there to describe the most fundamental sort of physics we've got. So it's like talking about... the Lego bricks that make us up."

Like Ex Machina, Devs also considers what could happen when a powerful tech titan stumbles into a potentially world-shattering discovery. "There were some other concerns [of mine], which have to do with the specific nature of some of the tech companies in terms of power: the kind of power they take for themselves, and also the power we confer onto them," Garland said.

Forest (Nick Offerman), the CEO of the quantum computing company Amaya in Devs, is the quintessential tech billionaire. Think Mark Zuckerberg -- if he had a secret division of Facebook tasked with decoding the nature of reality. (I wouldn't be surprised if this is actually happening on some level, to be honest.) By creating a powerful quantum machine, Amaya's "Devs" division is able to see any event in the past, as if it were a computer simulation. And that instantly opens the door to bigger questions: If it's effectively a view into the past, can it see the future? And what does that mean for free will?

"The thing that interested me about quantum computers was a specific idea," Garland said. "We've had binary computers, but we appear to live in a quantum mechanical world. And so what you get is binary computers attempting to emulate the conditions of quantum mechanics in their modeling systems, and if you had a quantum computer working in a quantum mechanical way ... you might be able to model it in in a much truer and more accurate way."

Garland views Amaya as a typical Silicon Valley success story. In the world of Devs, it's the first company that manages to mass produce quantum computers, allowing them to corner that market. (Think of what happened to search engines after Google debuted.) Quantum computing has been positioned as a potentially revolutionary technology for things like healthcare and encryption, since it can tackle complex scenarios and data sets more effectively than traditional binary computers. Instead of just processing inputs one at a time, a quantum machine would theoretically be able to tackle an input in multiple states, or superpositions, at once.

By mastering this technology, Amaya unlocks a completely new view of reality: The world is a system that can be decoded and predicted. It proves to them that the world is deterministic. Our choices don't matter; we're all just moving along predetermined paths until the end of time. Garland is quick to point out that you don't need anything high-tech to start asking questions about determinism. Indeed, it's something that's been explored since Plato's allegory of the cave.

"What I did think, though, was that if a quantum computer was as good at modeling quantum reality as it might be, then it would be able to prove in a definitive way whether we lived in a deterministic state," Garland said. "[Proving that] would completely change the way we look at ourselves, the way we look at society, the way society functions, the way relationships unfold and develop. And it would change the world in some ways, but then it would restructure itself quickly."

The sheer difficulty of coming up with something -- anything -- that's truly spontaneous and isn't causally related to something else in the universe is the strongest argument in favor of determinism. And it's something Garland aligns with personally -- though that doesn't change how he perceives the world.

"Whether or not you or I have free will, both of us could identify lots of things that we care about," he said. "There are lots of things that we enjoy or don't enjoy. Or things that we're scared of, or we anticipate. And all of that remains. It's not remotely affected by whether we've got free will or not. What might be affected is, I think, our capacity to be forgiving in some respects. And so, certain kinds of anti-social or criminal behavior, you would start to think about in terms of rehabilitation, rather than punishment. Because then, in a way, there's no point punishing someone for something they didn't decide to do."

Our ideas around guilt might change toward predicting what people might do in the future, a la Minority Report. That could lead to a world where we imprison someone forever because we've determined they can't be rehabilitated. But it could also save plenty of other people, according to Garland. Personal responsibility will mean something entirely new if we accepted a deterministic universe.

"The thing about that is, unlike a lot of these [complex philosophical topics], which often work in a counter-intuitive way... I think this particular idea around determinism actually dovetails quite closely with our experience of how the world works," Garland said. "It's very often the case that, say, if someone does something that makes us angry, the more we understand about that person, the less angry we get."

Now that Devs is off his plate, Garland has begun work on a new political FX series centered on civil disobedience. But he may not stay away from science fiction for long. “Years and years ago, I did a movie set in space [Sunshine]. And one day, I'd really love to go back and try and do that again.”